To illustrate some of the dangers the first Hill Country pioneers faced, I’m going to tell you the story of an early community called Strickling, and how it fits into Texas history.

Captain John Webster was a plantation owner in Virginia when Texas declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, but the stories he heard appealed to his adventurous disposition, and he sold his plantation to come to Texas. Bringing forty-four like-minded men with him, he joined the fight against the Mexicans. Almost half his men were killed and more were wounded, but Captain Webster survived the war and purchased a large tract of land along the North Fork of the San Gabriel River in what is now Burnet County.

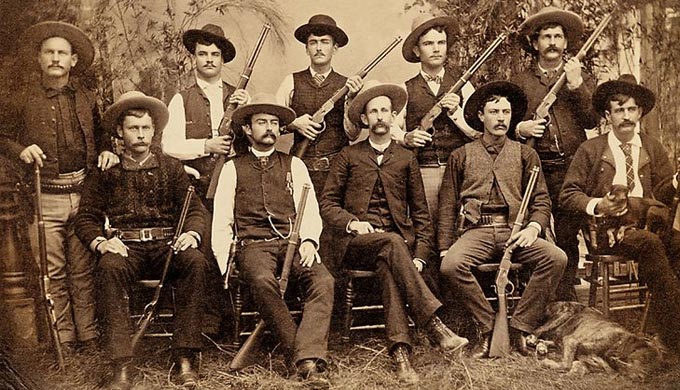

Under President Mirabeau B. Lamar, the Republic of Texas sent the Texas Rangers on an aggressive campaign to end Indian depredation and expand the frontier, and while Comanches still roamed the Hill Country freely, they had suffered a string of military losses.

Photo: stargazermercantile.com

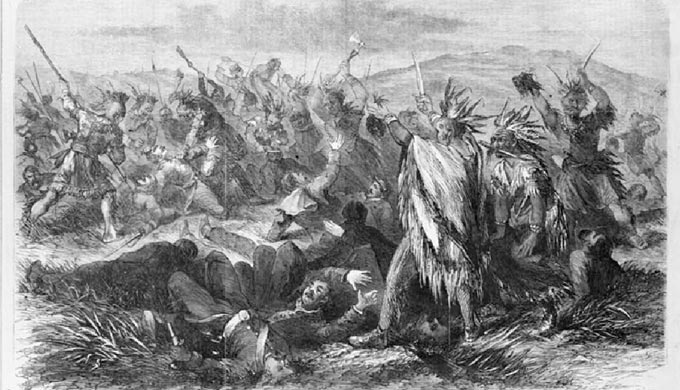

In the spring of 1839, Captain Webster took his family (his wife, a 10-year-old son and a 3-year-old daughter), thirteen men and four wagons north from Bastrop County to form a settlement on his new land. Another group was to follow with more wagons and a herd of cattle. Just six miles from the spot where Webster planned to build a fort, the settlers spotted a band of around 300 Comanche warriors, and turned back, hoping to reach the safety of Austin (which itself was still just a cluster of cabins). They were overtaken near Brushy Creek, and after a day-long battle all fourteen men were killed. Mrs. Webster and her two children were taken prisoner, and a wild celebration was held by the whole Comanche tribe at Enchanted Rock, in what is now Llano County.

Though many of their captives were tortured and killed, the Comanches had by that time collected about thirty prisoners. As their losses to the Texas Rangers mounted, some of their chiefs arranged peace talks with state officials in San Antonio, and promised (for a generous ransom payment) to return all the prisoners. Before the date of the meeting, however, the chiefs changed their minds, and decided to bring only one prisoner with them to the meeting. Fearing trouble, Mrs. Webster took her daughter, Virginia, and fled from the camp into the West Texas wilderness.

Photo: Wikipedia

The prisoner that the Comanches chose to return was 16-year-old Matilda Lockhart, who had been horribly tortured and abused during a two-year captivity. She was an intelligent girl who had quickly learned the Comanche language, and she was able to tell the Texans about the chiefs’ strategy and deception. Her report, combined with the sight of her disfigured face and scarred body, infuriated the Texans, who then informed the chiefs that they would remain as prisoners in San Antonio until all the white prisoners had been released. A fight immediately broke out, in which thirteen Comanche chiefs and at least seventeen family members were killed. The widow of Chief Buffalo Hump was sent to arrange the return of the white prisoners to San Antonio, but when she delivered the news to the Comanches, all the remaining prisoners were tortured to death in an orgy of furious revenge.

Despite her genteel Virginia upbringing, Mrs. Webster was a strong woman. Carrying her little daughter most of the 300-mile journey from Devil’s River to San Antonio, she traveled at night, avoiding marked trails and watering places and hiding during the day to escape detection. Nearly starved, and too weak even to cry out, she was discovered by a Mexican wagon train three miles from the city.

Photo: Wikipedia

In the meantime, hundreds of Comanche warriors had joined in outrage at the killing of their chiefs. They rode around San Antonio, deep into the settled area of Texas. John J. Linn of Victoria recalled the campaign in his 1883 memoirs: “We of Victoria were startled by the apparition presented by the sudden appearance of six hundred mounted Comanches in the immediate outskirts of the village.” The Comanches killed a few people and burned a house outside the town, but seemed more interested in stealing horses and looting the town than fighting a battle. They rode on to Linnville, where again they killed a few people and plundered the town.

By this time, the alarm had spread across Texas, and a group of Texas Rangers, regular army soldiers and local militia men met the Comanches at Plum Creek, near Lockhart. The Comanches were hampered by the enormous amount of loot they were carrying, and eyewitnesses described a “ludicrous” sight as the naked warriors donned fine cloth coats, top hats and fashionable shoes. They had spread calico over their horses, and trailed hundreds of yards of brightly colored ribbon. A huge herd of stolen horses also complicated their movements, and when the battle began, the Comanches were quickly routed. It was the beginning of the end for the Comanches, but the war would continue another forty years. During those forty years, no settler in the Texas Hill Country felt completely safe.

Photo: Sweet Lu (Pintrest)

This was the world which a few hundred unsuspecting German immigrants were about to enter, and any understanding of that world will help us appreciate their amazing accomplishments when we visit the charming town of Fredericksburg today.

Mrs. Webster never fully recovered from her ordeal, and she died just a few years later. But her courage and strength lived on in her young daughter; at age sixteen, Virginia Webster went back to the land that had cost her parents’ lives, and founded a small community in the wilderness of newly-formed Burnet County. The next year, she married Marmaduke Strickling (also spelled Strickland in some documents, including her memoirs!) and gave his name to the little town. One of the settlers was William Black, who built a private fort to protect the community from the Comanches.

Photo: texashistory.unt.edu

By 1856, Strickling was an important stage stop on the Austin to Lampasas route (according to the Handbook of Texas Online), and a post office was established in 1857. A school, a church, and several businesses prospered during the years that the town was on a major transportation route, but in the 1880s a decline began. The Austin and Northwestern Railroad bypassed Strickling in 1882, and when the stage line was discontinued later that decade, the town lost much of its vitality. Its population was reported as sixty in 1884 and in 1890, but by the mid-1890s its post office had been discontinued, and most of its residents had moved away. By 1900 the last store had closed. A cemetery was all that marked the site on county highway maps in the 1980s.

You can read some of Virginia Webster’s remarkable story (as told to the San Antonio Express-News in 1913) at: rootsweb.com. (She died in 1927, in Oakland, California.).