If you know Texas history, you know the story. At the second battle of Adobe Walls, buffalo shooter Billy Dixon used his Sharps rifle to shoot a Comanche chief off his horse at about 1,000 yards. With the chief dead, especially at such extreme range, the Comanches called it quits and left.

Public Domain

Public Domain

History

The Long Shot: The Battle for Texas at Adobe Walls

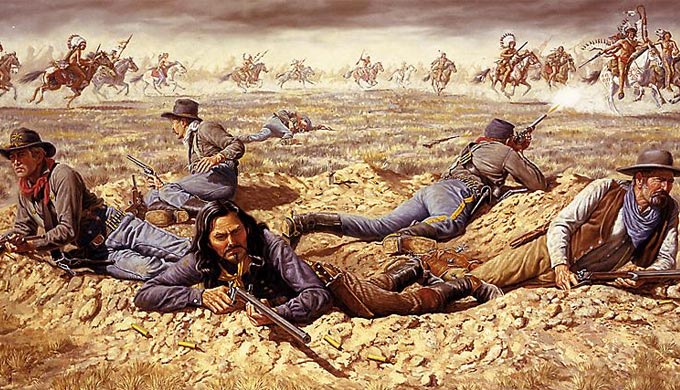

Image: June 1874 battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle, True West Magazine by Joe Grandee

So, did it happen?

We have two seemingly-related incidents:

#1: Billy Dixon fires his rifle at a group of Comanches atop a knoll nearly 1,000 yards away.

#2: One of the Comanches is seen to fall from his horse.

For years, this has been considered proof positive that Dixon shot the Comanche–but is it? Let’s ask–and answer to the best of our ability–three questions: First, could Dixon have done it? Is the shot in the realm of possibility, given the weapon and the man? Second, how likely is it that Dixon did it? Given the known abilities of human beings, is it at all likely that this happened? Third, did Dixon actually do it?

Question #1: Could Dixon have done it?

Photo: Billy Dixon, www.legendsofamerica.com

Dixon was shooting a Sharps long-range single- shot rifle. It was chambered either for Sharps’ famous ‘Big Fifty’ cartridge, a .50 caliber, 500 grain slug with a cartridge case 3½” long holding about 125 grains of powder, or for its only slightly smaller brother, the .45×3½, holding the same amount of powder and using about the same weight bullet, but of a slightly more ballistically efficient design.

While I don’t have at hand a ballistic table for either of those cartridges, I have one for the Big Fifty’s parent cartridge, the US Government Cal. 50 Rifle cartridge–the .50-70-450. The figures mean .50 caliber (bullet ½” in diameter), 70 grains weight of common rifle powder (1/100 of a pound of powder), and a bullet weighing 450 grains.

In 1871, the National Armory at Springfield, Massachusetts, published a 14-page booklet entitled Description and Rules for the Management of the Remington Navy Rifle, Model 1870. The last three pages of the booklet are titled “Memoranda of Trajectory &c.”

The rifle, a Remington rolling-block Model 1870 chambered for the government’s .50 caliber cartridge, was fired 1,882 times at ranges of from 200 to 1086 yards. The rifle was, for all but the extreme range tests, fired from a fixed rest 56″ above the ground–the height of the shoulder of a man standing 5’8″ tall (average height for a soldier of the day). The aiming point was a bullseye target, the center of which was 34″ above the ground–the height of the belt buckle or belly button of a 5’8″ man.

The targets were mounted on a frame 12′ wide and 18′ high. A total of 102 rounds were fired at 1086 yards. The aiming point at that range was ‘the center of the target board’–a point about 9 feet off the ground. The rounds actually struck somewhere on the target board 80% of the time.

The answer to question #1, then, is yes. The rifles of the day, even a rifle of considerably less power than Dixon’s, were capable of firing and hitting something at ranges even greater than Dixon’s shot.

Question #2: How likely is it that Dixon actually hit the target he shot at?

Image: “Study of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls” by Kim Douglas Wiggins

The problem here is range and human ability to estimate it. The average adult human being can, with experience and training, learn to estimate range fairly accurately out to about 500 yards. That’s where binocular vision fails and everything turns flat like a movie screen. It’s a function of how far apart the person’s eyes are in the head. Three-dimensional vision is necessary for accurate estimate of distances.

With practice– and Dixon had lots of practice–a person can train his or her brain to triangulate and estimate distances out to about 500 yards with an accuracy of about ±5%. That is, an estimate of 500 yards will be within 50 yards of being dead on–somewhere between 475 yards (-5%) and 525 yards (+5%). The ballistics tables for the .50-70 tell us that at 500 yards, on the falling end of the trajectory, there was ‘danger space’–that is, the bullet was low enough to hit a 5’8″ man somewhere between his forehead and his crotch–for a total of 77.5 yards, from 42 yards in front of him to 35.5 yards behind him. That’s well within the capability of an experienced shooter to estimate range and hit a man-sized target.

Photo: “Adobewalls”. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikipedia

At double that range? Beyond 500 yards ‘estimation’ becomes ‘guesstimation.’ We’re reduced to comparing sizes of objects. On a fairly flat, treeless area like the Adobe Walls battleground, there’s just not much to compare with. Still, an experienced hunter can estimate range with a fair amount of accuracy out to as much as a mile. The accuracy is nowhere near ±5% though. It’s more like ±10% at 600 yards to upwards of ±25% at 1000 yards or more.

Still, we’re dealing with a very experienced hunter here. We’ll give Dixon a margin of error of about ±15%, which is probably pretty generous. That’s a 300 yard margin of error–the actual range may be anywhere from 936 yards to 1236 yards. What margin of error does our ballistics table allow us at 1086 yards? Our danger space at that range is only 7 yards–21 feet. The bullet is coming almost straight down. The maximum height the bullet’s path rises above the line of sight–known as the ‘maximum ordinate’ in artillerymen’s terms–at a mere 700 yards is 87 feet. At 1086 yards, though the table doesn’t give it, the maximum ordinate, if it doesn’t exceed 100 feet, doesn’t miss it by much.

Dixon’s Sharps was considerably more powerful than the .50 Government cartridge, but it was still a black powder weapon pushing a very heavy bullet. Like all such, it had a trajectory like a rainbow. Even if Dixon’s rifle had as much danger space at 1000 yards as the .50-70 had at 500 yards–and it likely had considerably less–the danger space would still be less than a third of the margin for error in the very generous range-estimation ability we’ve given Dixon.

The answer to Question #2 must be, then, downright unlikely.

Question #3: Did Billy Dixon, in spite of the odds against it, actually hit what he shot at?

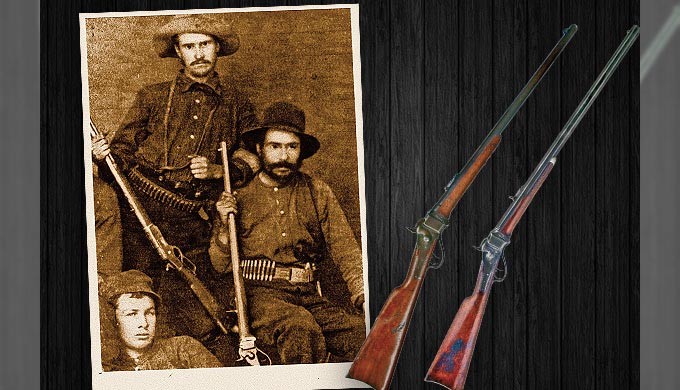

Photo: Ready for the hunt, the frontiersman at right packs an 1873 Winchester, while his companion (far right) holds a heavy, octagon-barreled 1874 Sharps. Courtesy of Herb Peck Jr. Collection from True West Magazine.

Well, for a long time everybody assumed he did. After all, he fired…there was a wait…and then a Comanche fell off his horse. Shortly afterward the Comanches quit the field and left. Even with the odds against him being almost impossibly high, Dixon must have hit the man.

For a long time nobody asked the Comanches what happened. When somebody finally got around to that, the answer was surprising. The Comanches had been in a pitched battle against forted-up whites for three days, a condition not to their liking at all. They’d lost a lot of warriors and all they had to show for it was three scalps taken the first day, one of them from a dog. They were holding a council of war on a knoll they considered completely out of range of the white men’s rifles, deciding whether or not to continue the fight. One of the chiefs was hit with a nearly- spent bullet that knocked him off his horse but did not wound him severely. They took this as a sign it was time to quit, and they did.

Please note–knocked off his horse by a nearly spent bullet. In our ballistic table for the .50-70 we find that its 450 grain bullet was capable of penetrating 5″ of seasoned pine lumber at 1086 yards. A bullet that can penetrate 5″ of seasoned pine lumber is capable of doing a lot more than simply penetrating a human body. It’s capable of killing the man it hits.

Photo: 1874 Sharps, Courtesy of Herb Peck Jr. Collection from True West Magazine.

Yet by Comanche testimony, their man was knocked off his horse and bruised by the bullet that hit him, but not severely injured. Dixon’s rifle would have had considerably more residual energy at 1000 or so yards than the much-lighter-loaded .50-70. It would have had the ability to penetrate considerably farther into seasoned pine than a mere 5″.

Answer to Question #3 is no. If the Comanche account of what happened on the knoll during their council of war is accurate, Dixon did not hit the man. If he had, the man would have been at the very least seriously wounded and most likely would have been killed. Well, Billy said it was a scratch shot. He was right.