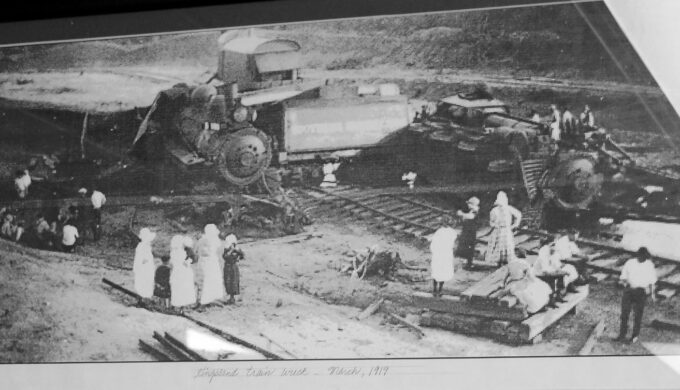

Photo: The fatal train wreck of 1919 symbolized the end of Kingsland’s railroad-based heyday

It was the advent of the automobile that ended Kingsland’s golden era; by 1913, cars had replaced the train as America’s favorite way to travel (although the first car didn’t arrive in Kingsland until 1915), and the Antlers Hotel was sold. A one-lane “wagon bridge” was built next to the railroad bridge across the Colorado River in 1914, and a new “Kingsland High School” (serving grades 1 through 11) was built in 1917, but Kingsland’s tourist industry faded away. As if signaling the beginning of the end for Kingsland’s railroads, a train came off the tracks at “Harwell Shoals, across the river at the rock quarry” in 1919. The ensuing wreck killed the engineer and shocked the town.

While the nation’s economy boomed through the 1920s, Kingsland’s economy nearly shut down. The hills and rivers that made Kingsland such an attractive place also made it almost inaccessible by road; rough, steep and winding one-lane dirt roads, interrupted by numerous gates, were the only ways in or out of Kingsland, and the road west to Llano was often made impassable by rising water in the Llano River. To get supplies, most Kingsland residents had to take the old “Fort Mason Crossing” (named for the military route from Burnet’s Fort Croghan to Fort Mason around 1850) north of town and travel the rough road across Backbone Ridge to Burnet. Tourists found it easier to reach other towns, located on the major highways. Most of Kingsland’s businesses, including Campa Pajama and the Antlers Hotel, were closed, and a fire destroyed most of the old buildings in 1922. The Antlers Hotel was purchased by Thomas Barrow in 1923 for use as a family retreat, and Kingsland’s population dropped to just 150 in 1925.

Muriel Barnett Jackson, who was born in Kingsland in 1910 and spent summers at her grandparents’ home there during her growing-up years, recalls hard times but good lives during those years. “People were poor, but didn’t know it,” she wrote decades later. “The whole town was like one big family. Most everyone owned their home and a little plot of land. Everybody had a cow and chickens and a hog to butcher in the winter; everybody had a garden and a few fruit trees. The rivers were full of fish, and the woods were full of deer, cotton tail rabbits, dove, quail and wild turkeys. Everyone shared, and nobody went hungry. Our entertainment was simple, but fun; Sunday School and church on Sundays, community singings, box suppers, play parties and an occasional dance at someone’s house who wasn’t a regular church-goer. We had picnics on the slab, we had ice cream suppers and watermelon parties; we went swimming and rode horses out at the Murchison Ranch. We often ran races and sometimes we had goat ropings.”

And it wasn’t all bad news; Mrs. Myrtle Wood, who was principal of Kingsland High School from 1923 to 1925, made it one of the best schools around, and brought cooking utensils and woodworking tools from home to teach home economics and shop classes. According to a letter published in the Burnet Bulletin in 1928, Kingsland still boasted “two business houses, a telephone office, three filling stations, two barber shops, a dance hall, a blacksmith shop and a ‘patent medicine’ drug store.” A road to Marble Falls had been built with donations from business owners in the two towns, and the letter reported that “several wagonloads of chickens from this community were shipped to Marble Falls last Wednesday.” Also, 200 railcar loads of gravel had been shipped by rail from a local gravel pit in the previous month. A 14-member 4-H Club was formed in Kingsland in 1933. County Commissioner Shirley Williams built the first “slab” across the Llano River after a flood washed the old “viaduct” away, making transportation to Llano a lot more predictable (but still interrupted regularly by high water). The construction of Buchanan Dam and Inks Dam provided work during the mid-thirties, and Kingsland enjoyed a brief period of prosperity; school enrollment grew with the arrival of itinerant workers and their families.

But when those dams were completed in 1937, most of the workers left; Kingsland was nearly a ghost town by the 1940s. Many of the young men who still lived here went off to fight in World War II; Llano County’s first casualty of the war was Roger Barnett of Kingsland (he had been aboard the U.S.S. Houston, which was sunk in a valiant attempt to stop the Japanese invasion of Java on February 28, 1942). Kingsland’s shrunken school system was consolidated with Llano’s in 1948; the once-proud “Kingsland High School” was torn down the following year. By then, the “business district” consisted mostly of a combination post office, store and filling station, and only about a dozen houses marked the location of the once-booming resort town.