History

Railroads in the Hill Country

By John Hallowell

Railroads turned some small Hill Country towns into boomtowns, but sounded a death knell for others. Either way, the course of Hill Country history was forever altered. The arrival of the railroad, beginning in the 1880s, changed the course of Texas Hill Country history. No longer could the rugged landscape keep civilization at bay. Fifty years earlier (in 1830), the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had established the first network of rail service in the eastern United States, and its 536 miles of track played an important role in the Civil War. After the war, the nation focused its energy on creating a transcontinental railway – a project which was completed in 1869. In the meantime, railroads were spreading across east Texas, arriving at Austin and Waco in 1871, then creating a major inland city at Dallas, when north-south and east-west railroads met there in 1873. San Antonio finally obtained rail service in 1877.

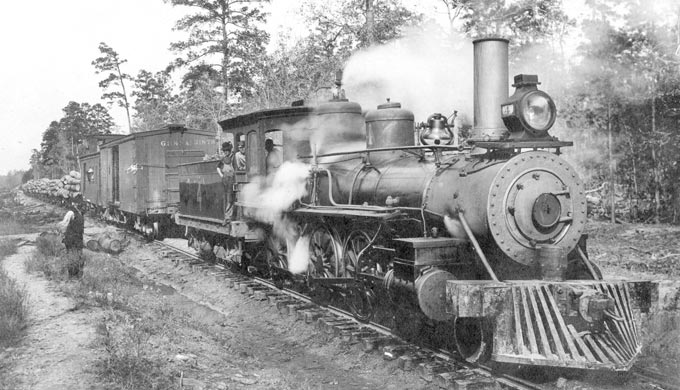

Photo: texashistory.unt.edu

In 1878, rail service was extended north from Austin to Georgetown, on the eastern border of the Hill Country. In 1880, service was introduced from San Antonio to New Braunfels; that line was joined from the north by the International-Great Northern Railroad through Austin and San Marcos in 1881. Also that year, a line was built west from San Antonio through Castroville, Hondo and Uvalde – a line at the edge of the hills which still serves as the southern boundary of our Hill Country map.

Photo: roundrocktexas.gov

But the first real venture into the heart of the Hill Country was the rail line built by the the Austin and Northwest Railroad company from Austin to Burnet in 1882. That line made Burnet into a Hill Country boomtown as a shipping center for all towns west, and spawned a brand-new town — called Bertram, for one of the railroad executives – along the way. Also in 1882 the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway built a line from Temple to Lampasas, bringing commerce and tourism to the town famous already for the healthful qualities of its sulphur springs. Lampasas was transformed from a rowdy cattle town into a popular and elegant resort, sometimes called the “Saratoga of the South.”

Photo: en.wikipedia.org

The railroad was extended from Burnet to Granite Mountain (near Marble Falls) in 1884 to simplify shipping stone for the construction of the state capitol, then again to Kingsland and Llano in 1892, where an iron-and-precious-metals boom was already underway. In the meantime the rail line had been extended from Lampasas to Brownwood and beyond in 1885, leading to the establishment of several towns, including Lometa, Goldthwaite and Mullin, along the way. Another railroad came to Brownwood through Comanche from the north in 1891, making the previously sleepy little town into a major regional center. In 1887, another track had been built from San Antonio, through Boerne and Comfort, to Kerrville, where steep hills and deep canyons squelched plans for further extensions.

Photo: Flickr/SMU Central University Libraries

A decade or more passed before the railroads expanded again in 1903, this time from Brownwood southwest to Brady, which also experienced a period of explosive growth. In 1907, railroad service came to Hamilton (from Stephenville), and in 1911 two more extensions were built: one from Lometa, going west through San Saba, Richland Springs, Rochelle, Brady and eventually Eden; the other from Brady, southwest to Menardville (which changed its name to the simpler “Menard” in deference to the railroad’s sign-painters.

Photo: Flickr/Dwayne and Maryanne

The last (and most complicated) Hill Country railroad was the line from Comfort to Fredericksburg, built in 1913. Fredericksburg had long been the Hill Country’s largest town, and several attempts had been made to have accessible by railroad. Construction had started and stopped on tracks north to Llano (in 1889) and south to Comfort or Kerrville (in 1909). Because it crossed the high divide between the Guadalupe and Pedernales Valleys, the southern route required high trestles and a 920-foot tunnel along the way. The line was precarious throughout its short life, and was closed in 1929, when highways from the east and the south made Fredericksburg accessible by truck. Blanco, Mason and Kimble Counties were never reached by a railroad. The popularity of the automobile and improved road construction led to a sharp decline in rail travel during the 1930s, and many of the passenger routes closed down in the 1940s and 50s. Railroad depots were neglected for decades, and some were torn down. In recent years, efforts have begun to restore these symbols of a bygone era. Several have been used as restaurants, visitor centers or museums.