After 110 million years, the mummy of a plant-eating nodosaur was found practically intact in the oil sands of northern Alberta, Canada. With its fossilized skin and the contents of its gut still, in effect, whole, it’s been extraordinarily well-preserved, and its face remains frozen in a glare one can only begin to speculate on.

How the dinosaur died isn’t known. The nodosaur was a land-dwelling creature; an armor-plated plant-eater. Somehow its corpse would end up at the bottom of what was an ancient sea, where minerals were able to keep the body largely intact and eventually turned it into a fossil (similar to the amazing finds that have taken place in Texas, for the same reasons.) It was originally unearthed in 2011 when a shovel operator in a mine found a block that had a funny pattern to it and contacted a geologist. Scientists quickly recognized it as one of the most well-preserved specimens of its kind, and have been working to study and continue its preservation since.

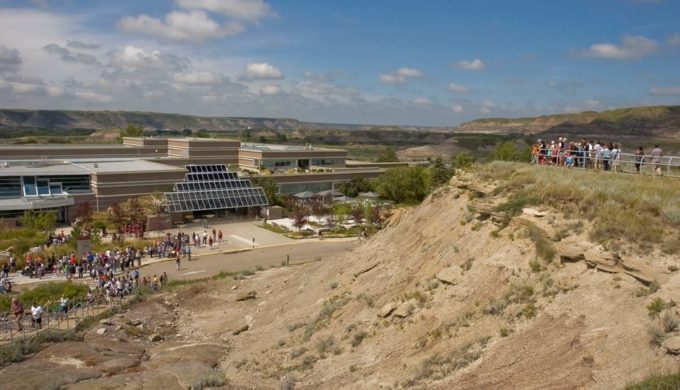

Photo: Facebook/Royal Tyrrell Museum

In an interview with the New York Times from May of this year, Don Brinkman, director of preservation and research at the Royal Tyrrell Museum located in Drumheller, Alberta, noted, “It’s basically a dinosaur mummy — it really is exceptional.” Coming from the Millennium Mine in northern Alberta, the area it was located in had, at one time, been a giant seabed. The area has been rich with fossils as far back as there have been records of such things.

Photo: Facebook/Nodosaur

Photographed for the June 2017 issue of National Geographic, the dinosaur “mummy” went on display in Drumheller in May. Within the province of Alberta, any fossil that is discovered is deemed the property of the government, and not of the landowner on whose property it was found. Many are found due to erosion, however, mining is a large industry in that part of Canada, and has proven to be a godsend for paleontologists. They work as best they can with the industry in order that future finds aren’t neglected as a result of bad partnerships. A boon for his industry, Brinkman identified, “These are specimens that would never be recovered otherwise. We get two or three significant specimens each year.”